OUR OFFICE

Based near downtown Los Angeles, TWA is both a design studio and an intellectual and creative hub. Our team of architects and designers are driven to change the course of architecture and the cities we live in.

Read More

The atmosphere at TWA is open, energetic, and rooted in curiosity:

What should architecture's role in society be?

How can buildings protect the earth?

What does the future look like?

We Design In Real Time

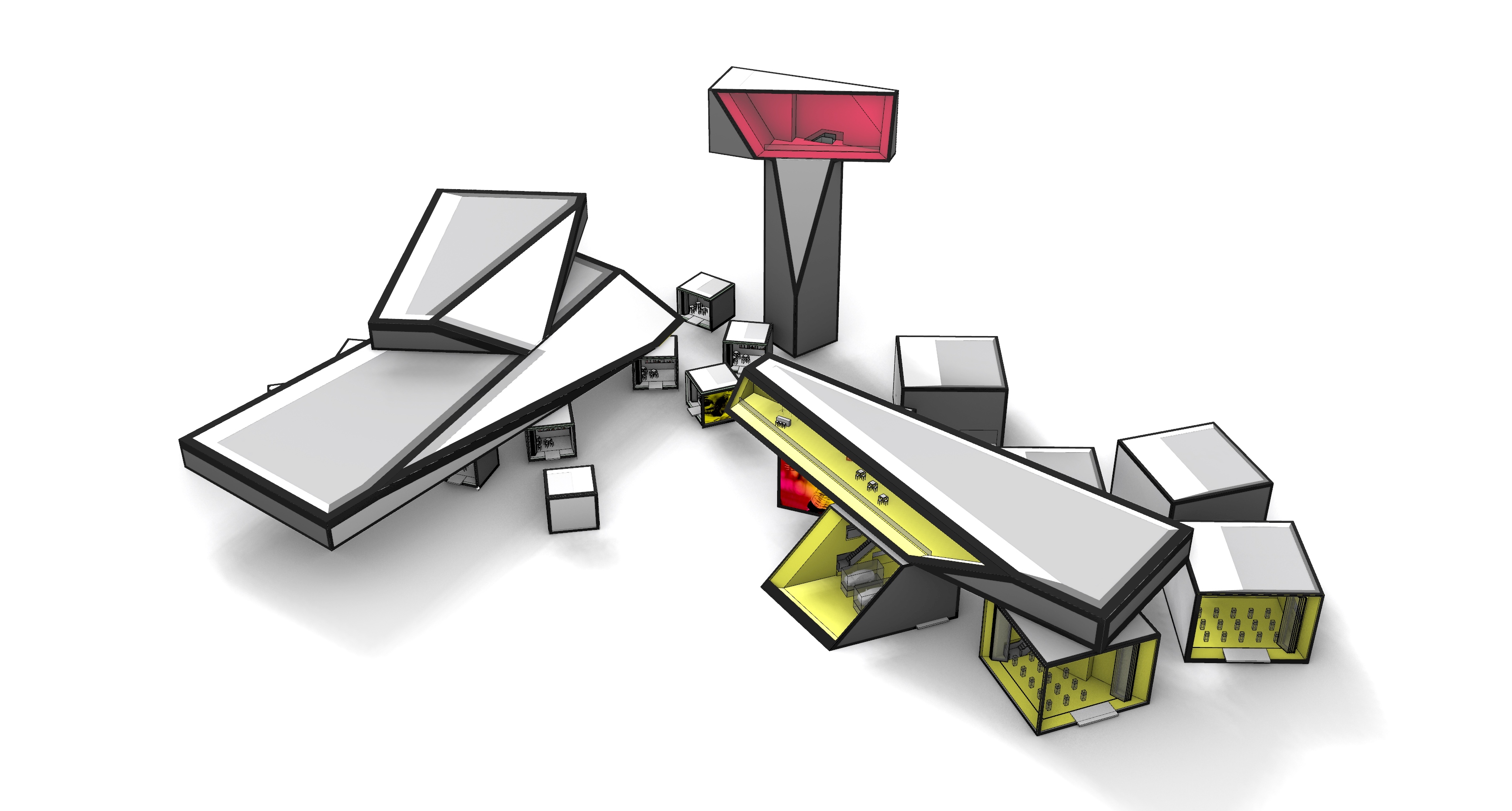

‘Live Modeling’ sessions form the core of our internal creative process, in which the full range of formal possibilities each project offers can be explored collaboratively. Our office is broken up into 3D modeling bays we call “Thunderdomes,” which are encircled by huge television screens and driven by banks of computers and 3D printers, so that everyone in the team can see what everyone else is doing.

Read More

Thunderdomes were first developed to help build teamwork and deliver competitions quickly, but now they are our standard method of doing all of our creative work at TWA.

Clients, engineers, and other project stakeholders are invited to participate in this open process at key moments, creating opportunities for consensus to develop and design decisions to be made quickly and in the most informed manner. Design ceases to be a private, tortured affair, but rather a public screening and testing of ideas that feels light and contemporary. Nothing is sacred; everything is thrown into the scene, scaled, rotated, copied, altered, chopped in two, or erased without hesitation.

In parallel to this, TWA has developed its own signature drawing techniques based on 3D models, including 3D cutaway and axonometric drawings and detailed, easy-to-understand technical animations. These are used to understand and visualize all the elements of each design in a way that showcases massing, interiors, structure, facades, circulation, landscape, lighting, details, and the whole social world of the building at the same time. We use these at concept design stage for stakeholders, and also at construction documents stage for builders, to communicate all the defining aspects of the project.

Clients, engineers, and other project stakeholders are invited to participate in this open process at key moments, creating opportunities for consensus to develop and design decisions to be made quickly and in the most informed manner. Design ceases to be a private, tortured affair, but rather a public screening and testing of ideas that feels light and contemporary. Nothing is sacred; everything is thrown into the scene, scaled, rotated, copied, altered, chopped in two, or erased without hesitation.

In parallel to this, TWA has developed its own signature drawing techniques based on 3D models, including 3D cutaway and axonometric drawings and detailed, easy-to-understand technical animations. These are used to understand and visualize all the elements of each design in a way that showcases massing, interiors, structure, facades, circulation, landscape, lighting, details, and the whole social world of the building at the same time. We use these at concept design stage for stakeholders, and also at construction documents stage for builders, to communicate all the defining aspects of the project.

Deep Collaboration

The role of the Architect is changing fast, and we do not accept that the relationship between expert disciplines should be confrontational—everyone loses. Our leadership experience in building some of the world’s most complex structures gives us the knowhow – and humility – to understand the concerns of our engineering and construction partners.

Read More

Read More

Whenever possible we use a design-assist (ECI) model of project delivery, where contractors, engineers, and architects begin working together early in the design process, making outcomes more integrated and reducing risk for the owner.

TWA takes special interest in structure, facades, lighting, media, and landscape, acting as an active collaborator with our subconsultants, leading the design and setting boundaries and goals for each project. This brings collaborators into our decision-making approach and helps foster the sense of shared achievement.

Currently, hundreds of developers, owners reps, architects, engineers, specialty consultants, and builders are focused on the realization of the Qiddiya Performing Arts Centre, our largest project to date. TWA leads this project together with our executive partner BSBG, Dubai, with whom we have a longstanding relationship. Our team has achieved the highest standard of project leadership, risk reduction, and design excellence, with many more projects to come.

TWA takes special interest in structure, facades, lighting, media, and landscape, acting as an active collaborator with our subconsultants, leading the design and setting boundaries and goals for each project. This brings collaborators into our decision-making approach and helps foster the sense of shared achievement.

Currently, hundreds of developers, owners reps, architects, engineers, specialty consultants, and builders are focused on the realization of the Qiddiya Performing Arts Centre, our largest project to date. TWA leads this project together with our executive partner BSBG, Dubai, with whom we have a longstanding relationship. Our team has achieved the highest standard of project leadership, risk reduction, and design excellence, with many more projects to come.

The Power of Models, and Their Parts

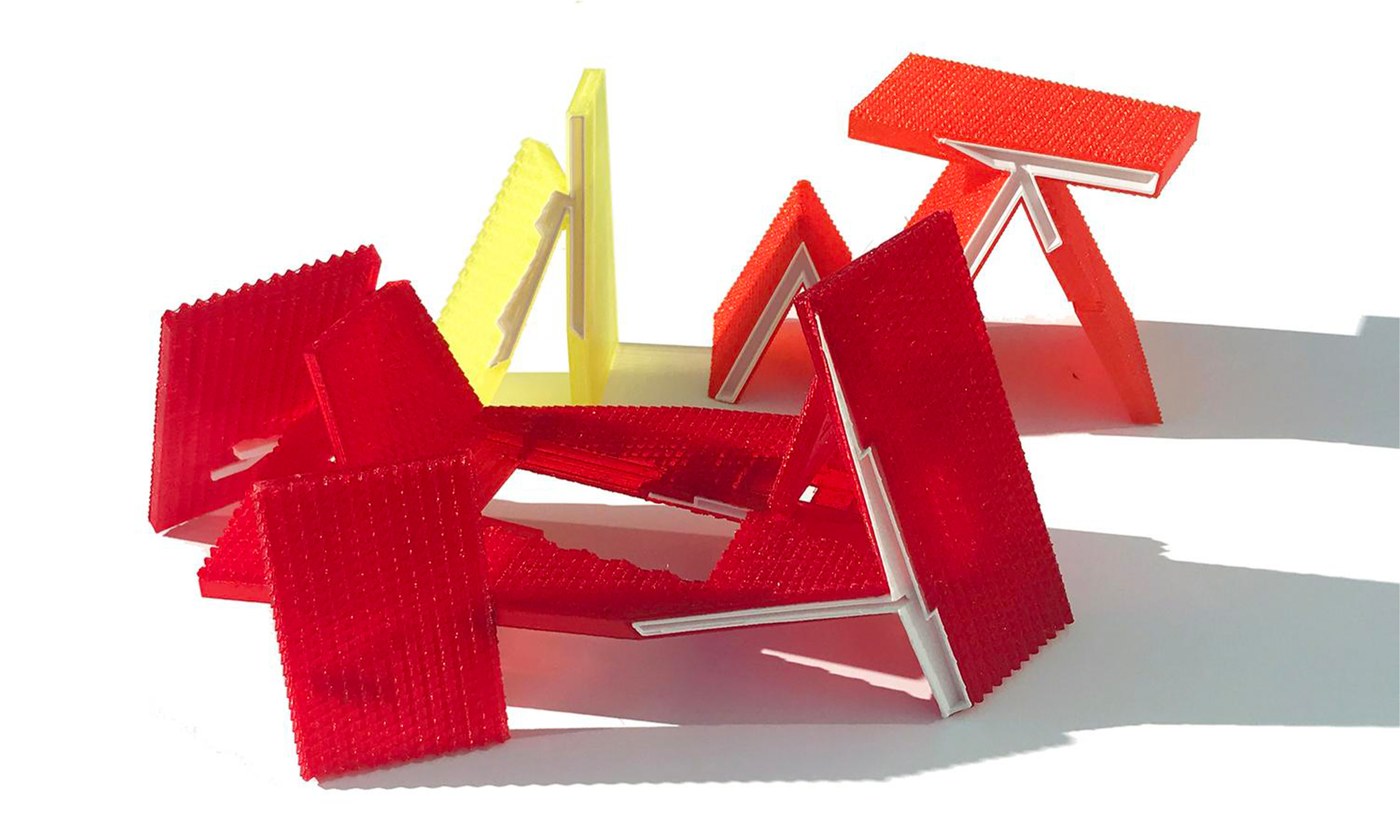

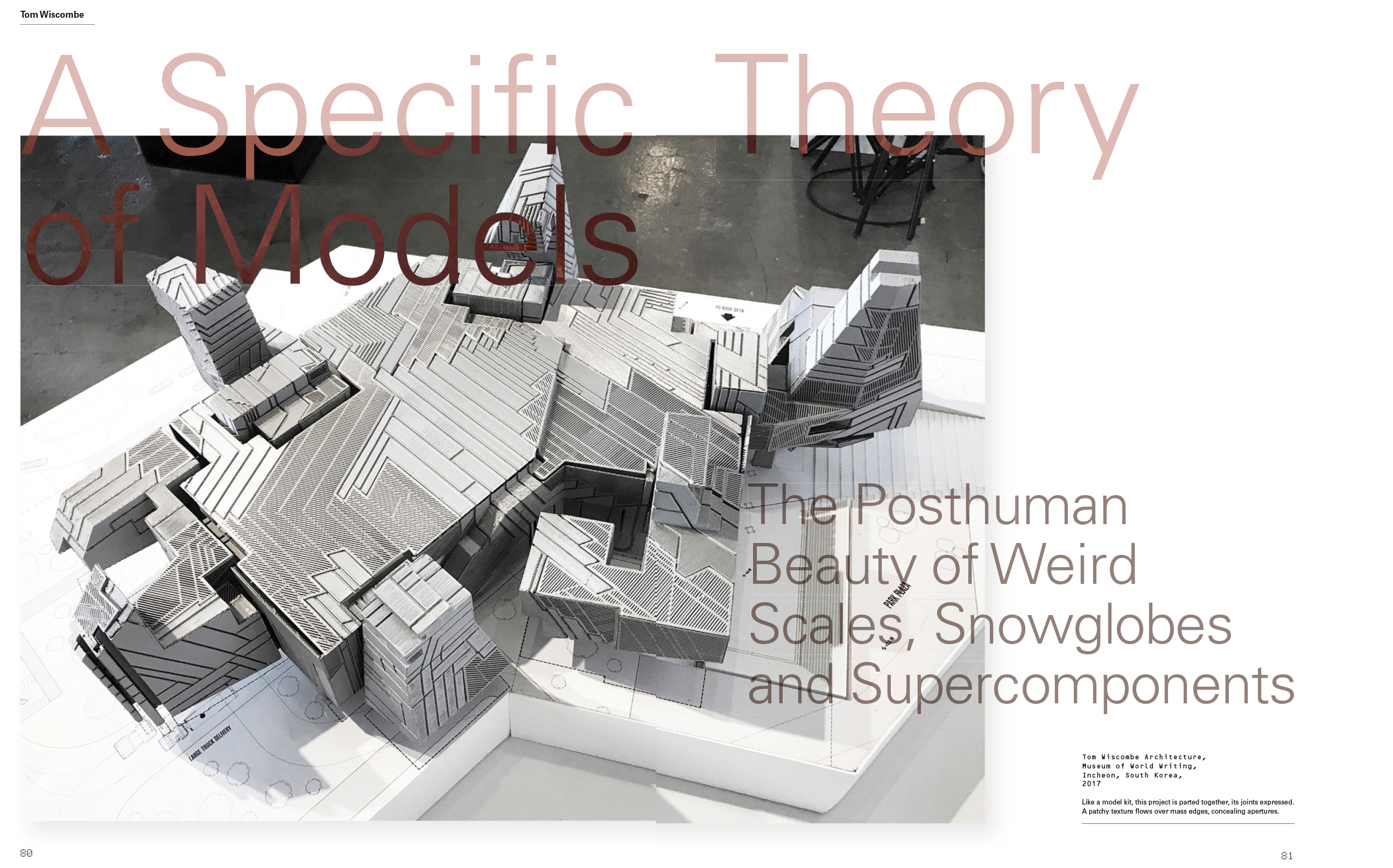

We started 3D printing in plastic at TWA a couple decades ago, in many colors and translucencies, attempting to control and design the inevitable joints between small parts. Over time, we realized that this mode of working was influencing our general approach to architecture, which actively celebrates discrete parts and joints between them.

Read More

The idea of architectural “Metaseams” and “supercomponents” emerged, referring to our desire to design both joints and very large parts, potentially for pre-fabrication, but not necessarily. These terms are now common parlance around the office, with the approach regularly finding its way into our built work, either as actual joints and components, or as fictitious features with the same visual effect.

There is a lot of craft in 3D printing that involves planning, subdividing, removing detail, adding snap-fit or mortise and tenon joints for structural continuity, prototyping, and so on. This work directs your attention to tectonics, sometimes with shocking discoveries of what might be possible in construction at full scale. We are intrigued by the messy, low-tech, and inexact territory around 3D printing, not the ideology of effortless production and perfection we always hear about in relation to 3D printing and architecture in the media.

While it may very well be possible to print full-scale integrated components for buildings in the near future-- as it has become possible in the automotive industry-- the real benefit of 3D printing/ rapid prototyping in architecture is as a form of speculation about building. Experimentation in miniature models and prototypes can produce wild leaps of imagination about the future of tectonics that the slow progress of industry cannot provide. As we know, industry is laggy by nature due to massive costs to shift away from currently profitable processes, so front-line work with little models is probably more likely to have immediate effect on the future than waiting around!

There is a lot of craft in 3D printing that involves planning, subdividing, removing detail, adding snap-fit or mortise and tenon joints for structural continuity, prototyping, and so on. This work directs your attention to tectonics, sometimes with shocking discoveries of what might be possible in construction at full scale. We are intrigued by the messy, low-tech, and inexact territory around 3D printing, not the ideology of effortless production and perfection we always hear about in relation to 3D printing and architecture in the media.

While it may very well be possible to print full-scale integrated components for buildings in the near future-- as it has become possible in the automotive industry-- the real benefit of 3D printing/ rapid prototyping in architecture is as a form of speculation about building. Experimentation in miniature models and prototypes can produce wild leaps of imagination about the future of tectonics that the slow progress of industry cannot provide. As we know, industry is laggy by nature due to massive costs to shift away from currently profitable processes, so front-line work with little models is probably more likely to have immediate effect on the future than waiting around!

Our Creative Space

We have a uniquely open, indoor/outdoor creative office space located in the historic American Cement Building near downtown Los Angeles. Our office represents the best of design and architecture, and positively influences our whole working culture.

Read More

Some call our office the “toy factory” because of the thousands of multicolor models residing here in every room and in glass vitrines. Supporting that is our 3D printing farm with 30 printers working all at once. Our entire office is littered with models, both huge and tiny.

People

Tom Wiscombe, AIA, NCARB

Founder + Principal

Tom Wiscombe, born in 1970, is Principal and Founder of Tom Wiscombe Architecture (TWA) in Los Angeles. His work is known for its powerful massing, alluring graphic qualities, and tectonic inventiveness, all underwritten by contemporary ecological thinking. He combines his renowned design expertise with a deep knowledge of construction and project delivery — gleaned from a thirty-year professional career — to create projects with the highest level of care and craft.

Tom’s work is radical in its treatment of architectural entities like ground, massing, interior, circulation, apertures, and ornament as independent objects within loose, curated collections, rather than as incomplete parts of a unified, singular whole. This approach stems from his influential theory of the flat ontology of architecture, which imagines architecture —and the world— as a set of discrete, lively entities that relate to each other in democratic rather than derivative ways. This allows his practice to move beyond received hierarchies of big to small, part to whole, and existing to new, and toward a deeply ecological understanding of buildings, cities, and landscapes.

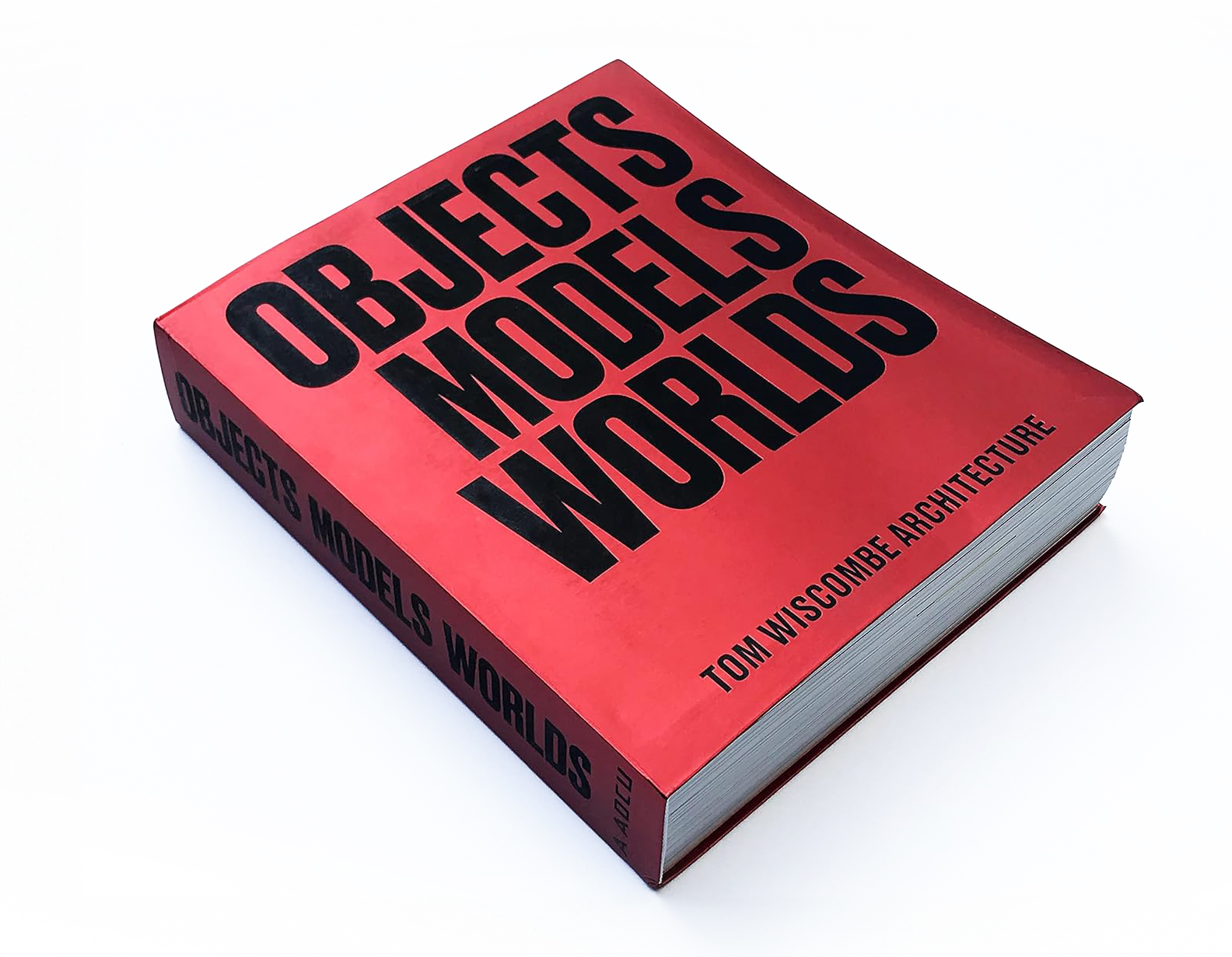

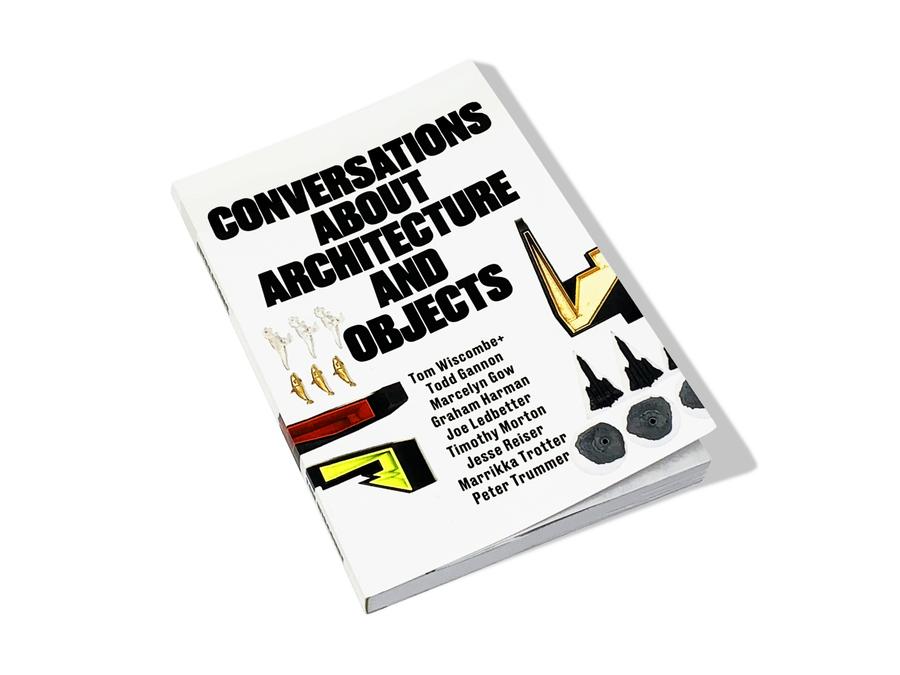

Tom is a leading voice in contemporary design culture, speaking, writing, and organizing discourse around the ideas of today. His 2021 monograph, Objects Models Worlds, captures the breadth of his practice and ideas.

Tom’s work is radical in its treatment of architectural entities like ground, massing, interior, circulation, apertures, and ornament as independent objects within loose, curated collections, rather than as incomplete parts of a unified, singular whole. This approach stems from his influential theory of the flat ontology of architecture, which imagines architecture —and the world— as a set of discrete, lively entities that relate to each other in democratic rather than derivative ways. This allows his practice to move beyond received hierarchies of big to small, part to whole, and existing to new, and toward a deeply ecological understanding of buildings, cities, and landscapes.

Tom is a leading voice in contemporary design culture, speaking, writing, and organizing discourse around the ideas of today. His 2021 monograph, Objects Models Worlds, captures the breadth of his practice and ideas.

Previous Built Projects

BMW World

Location: Munich, Germany

Area: 72,000 sm

Completed: 2007

Chief Designer for Coop Himmelblau

Location: Munich, Germany

Area: 72,000 sm

Completed: 2007

Chief Designer for Coop Himmelblau

Museum of Confluences

Location: Lyon, France

Area: 40,000 SM

Completed: 2014

Chief Designer for Coop Himmelblau

Location: Lyon, France

Area: 40,000 SM

Completed: 2014

Chief Designer for Coop Himmelblau

UFA Cinema Palace

Location: Dresden, Germany

Area: 7,400 SM

Completed: 1998

Chief Designer for Coop Himmelblau

Location: Dresden, Germany

Area: 7,400 SM

Completed: 1998

Chief Designer for Coop Himmelblau

Jamie Norden

Senior Associate

Jamie Norden is a Senior Associate at TWA, bringing over thirty years of experience working at the top of the global architectural field. His experience leading teams through the delivery of large complex architecturally significant projects make him an incomparable asset to the team at TWA. He works hand-in-hand with Principal Tom Wiscombe on project design and design management, business development, and team building.

Previous to joining TWA, Jamie spent two decades at Gehry Partners leading teams on iconic cultural projects such as the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, and the Facebook Campus in Menlo Park, California.

Previous to joining TWA, Jamie spent two decades at Gehry Partners leading teams on iconic cultural projects such as the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, and the Facebook Campus in Menlo Park, California.

Previous Built Projects

Guggenheim Abu Dhabi

Location: Abu Dhabi, UAE

Area: 30,000 sm

Target completion: 2026

Senior Associate for Gehry Partners

Location: Abu Dhabi, UAE

Area: 30,000 sm

Target completion: 2026

Senior Associate for Gehry Partners

Facebook Campus

Location: Menlo Park, CA

Area: 430,000 SF

Completed: 2018

Senior Associate for Gehry Partners

Location: Menlo Park, CA

Area: 430,000 SF

Completed: 2018

Senior Associate for Gehry Partners

Marrikka Trotter, Ph.D, LEED

Senior Associate

Marrikka Trotter is Associate in charge of Business Development and Client Relations at Tom Wiscombe Architecture (TWA) in Los Angeles. She is a prominent voice in contemporary design culture, speaking, writing, editing, publishing, and organizing venues for architectural and urban theory and criticism today. Her award-winning scholarship runs the gamut from the history of intellectual, imaginative, and technical intersections between architecture and geology to big-picture provocations on architecture and ecology today.

Marrikka also brings over twenty years of practice experience to her engagement with architectural ideas, allowing her to interface with emerging opportunities and technical developments within the discipline with ease. She balances a commitment to greater equality and justice in the world with the conviction that innovative and breathtaking architecture matters more today than ever.

Marrikka also brings over twenty years of practice experience to her engagement with architectural ideas, allowing her to interface with emerging opportunities and technical developments within the discipline with ease. She balances a commitment to greater equality and justice in the world with the conviction that innovative and breathtaking architecture matters more today than ever.

Kam Ku, AIA

Senior Project Architect

Kam has been working as a Project Architect/Manager for the past 30 years. He brings an unparalleled depth of technical knowledge of all engineering disciplines, constructability, and project documentation. He is licensed in the state of California and is a member of the AIA. He previously worked for Gensler on large domestic and overseas projects, on project types including cultural, commercial, educational, hospitality, mixed-use, retail and entertainment His specialty is high-rise hospitality and retail projects.

Previously, Kam founded a design collective, OCDC, to work on research and competition projects. It was active from 1998 to 2016, producing 50+ projects, and received many design awards. He drew design directions from multidisciplinary practices such as industrial, graphic, and transportation design, experimenting with many digital design softwares and fabrication techniques intended for other design disciplines.

Previously, Kam founded a design collective, OCDC, to work on research and competition projects. It was active from 1998 to 2016, producing 50+ projects, and received many design awards. He drew design directions from multidisciplinary practices such as industrial, graphic, and transportation design, experimenting with many digital design softwares and fabrication techniques intended for other design disciplines.

Jordan Micham

Design Manager

Jordan has a B.S. in Architecture from the University of Cincinnati, and an M.Arch. II from SCI-Arc. He has worked with Patterns, Oyler Wu, and RIOS, building his expertise in building modeling, engineering systems, and consultant coordination.

Jordan is a key leader in the Design Team here at TWA, responsible for the design and coordination of structure and MEP disciplines for large, complex projects. He is a natural communicator and is able to merge design and technical criteria together both in-house and in his thoughtful outreach to engineers and other consultants.

Jordan also leads competition teams at TWA, for large and complex public realm and entertainment projects in the Middle East.

Jordan is a key leader in the Design Team here at TWA, responsible for the design and coordination of structure and MEP disciplines for large, complex projects. He is a natural communicator and is able to merge design and technical criteria together both in-house and in his thoughtful outreach to engineers and other consultants.

Jordan also leads competition teams at TWA, for large and complex public realm and entertainment projects in the Middle East.

Binghao Yao

Senior Designer

Binghao Yao came to architecture through an early love of drawing and woodworking and his affinity for science and technical innovation. After earning his Bachelor of Architecture degree from Soochow University in Suzhou, China, Binghao pursued advanced education in the United States, earning his professional Master of Architecture degree from the University of California at Berkeley.

With extensive international competition experience and experience at high-profile offices, Binghao brings strong design skills, the ability to meet tight deadlines, and sophisticated graphic ability to the table at TWA. Bing is a natural leader at TWA, driving design teams through complex design tasks and leading major competitions for large-scale entertainment projects, with flair and good humor.

With extensive international competition experience and experience at high-profile offices, Binghao brings strong design skills, the ability to meet tight deadlines, and sophisticated graphic ability to the table at TWA. Bing is a natural leader at TWA, driving design teams through complex design tasks and leading major competitions for large-scale entertainment projects, with flair and good humor.

Shervin Hashemi

Senior Designer

Shervin holds a Bachelor of Architectural Engineering with Honors and a Masters of Architecture from the Pratt Institute in New York, and a Bachelor of Architectural Engineering with honors from the University of Tehran. He previously worked at Asymptote in New York, and TWA before that. He brings professional experience on residential and commercial projects as well as strong compositional skills and an obsessive attention to detail.

Shervin also brings to TWA an interest in Landscape Architecture, and has been project lead on landscape exercises so large they verge on terraforming. Shervin has been Senior Designer on many TWA competition projects, including on two Performing Arts Theaters in the Middle East.

Shervin also brings to TWA an interest in Landscape Architecture, and has been project lead on landscape exercises so large they verge on terraforming. Shervin has been Senior Designer on many TWA competition projects, including on two Performing Arts Theaters in the Middle East.

Niyousha Zaribaf

Senior Designer

With a Bachelor of Science and a Master of Architecture from Pratt Institute in New York City, Niyousha brings strong previous experience to her work at TWA. Her design work, influenced by her previous years at SOM, is precise and modern, supporting TWA’s repertoire of raw, simple, powerful forms.

Niyousha is in charge of major components of ongoing cultural projects, including theater design, structural design, and interior design. She works between Revit and Rhino, bridging between the Design and Technical Teams at TWA, developing sophisticated revit documentation and drawing sets.

Niyousha is in charge of major components of ongoing cultural projects, including theater design, structural design, and interior design. She works between Revit and Rhino, bridging between the Design and Technical Teams at TWA, developing sophisticated revit documentation and drawing sets.

Annika Ohta

Office Manager

Annika is a committed administrator and team builder with a wide breadth of knowledge about operations, management, and human resources. Having previously worked at Goldman Sachs in Asset & Wealth Management, she brings to TWA total professionalism and an understanding of what it takes to keep a large organization running smoothly.

She works closely with the Principal on day to day operations, hiring, staff relations, accounting, billing, writing, and public relations. Her humor, care, and focus on the team’s well-being make TWA a better organization.

She works closely with the Principal on day to day operations, hiring, staff relations, accounting, billing, writing, and public relations. Her humor, care, and focus on the team’s well-being make TWA a better organization.

Dheer Talreja

Computational Designer

Dheer Talreja holds a Bachelor of Architecture degree from NIRMA University in Ahmedabad, India, and a Master of Architecture II degree from the Southern California Institute of Architecture. His experience includes residential and commercial projects at a variety of scales with a focus on digital visualization, fabrication, and technical drawings.

Dheer is a technician by nature, keeping our sophisticated office running with the latest computer and 3D printing equipment, and administering our software, protocols, security, and training. He is also in charge of our 3D printer farm with over 30 printers, leading the office’s production of small and large models of complex projects, and customizing workflows to create unique material effects and features.

Dheer is a technician by nature, keeping our sophisticated office running with the latest computer and 3D printing equipment, and administering our software, protocols, security, and training. He is also in charge of our 3D printer farm with over 30 printers, leading the office’s production of small and large models of complex projects, and customizing workflows to create unique material effects and features.

Alvin Li

Senior Job Captain

Hailing from Los Angeles, California and receiving his Bachelor’s degree in Architectural Design from the University of Southern California, Alvin is known as a leader and team coordinator, often serving as the connection point between our Rhino and Revit teams. Alvin is responsible for site, landscape, and public realm documents for large cultural projects, which he executes with charm and accuracy. Alvin is a BIM expert, supporting our Technical Team on TWA BIM standards and families.

Iris Gu

Project Designer

With a Master of Science and Advanced Architectural Design from the University of Pennsylvania, Iris Gu is a hyper-focused and talented designer, able to bridge between structure, plan, and function.

She works with programmatic layouts, integrating technical and design requirements, materiality, lighting, and guest experience. Iris is often involved in developing spaces for exhibition, food and beverage, hospitality, and retail. She works closely with our structural, MEP, and lighting teams to create interiors that are fully coordinated.

She works with programmatic layouts, integrating technical and design requirements, materiality, lighting, and guest experience. Iris is often involved in developing spaces for exhibition, food and beverage, hospitality, and retail. She works closely with our structural, MEP, and lighting teams to create interiors that are fully coordinated.

Panjing Zhu

Project Designer

Panjing graduated from the UPENN Master’s Program, and has a B.Arch. from Xiamen University. At TWA, she works on a variety of project aspects, including facade development, landscape, and programming. Her work is very precise but also very loose and playful, which makes her a great and rare asset for TWA.

Panjing also works on international competitions, where she does creative massing solutions for large building and neighborhood-scale projects.

Panjing also works on international competitions, where she does creative massing solutions for large building and neighborhood-scale projects.

Chenglu “Lu” Xue

Project Designer

Chenglu earned a Master of Science in Advanced Architecture Design from the University of Pennsylvania, and a Bachelor of Architecture from Tianjin University in China. He has an amazing eye and ability to enliven everything he works on. He often does our “world diagrams” which capture TWA’s architecture in a social mode, filled with inhabitants and life and forests and everyday things.

Chenglu works on large project components such as glazed lobbies, circulation systems, structure, egress, and accessibility. He also is involved in media and lighting aspects of projects, including speciality, interactive systems, large-scale video projections, and custom lanterns.

Chenglu works on large project components such as glazed lobbies, circulation systems, structure, egress, and accessibility. He also is involved in media and lighting aspects of projects, including speciality, interactive systems, large-scale video projections, and custom lanterns.

Matt Scholtz

Junior Designer

Matt holds a B.Arch. from the Southern California Institute of Architecture.

At TWA he is focused on design model production using our 3D printing farm, in collaboration with our CTO/ Model Supervisor. He is currently working on various international gigaprojects.

Recognition & Awards

TWA wins the 2025 World Architecture Festival Future Cultural Award in Miami

for the Qiddiya Performing Arts Centre2025

Fast Company names TWA one of the World’s 10 Most Innovative Architecture Firms in 2022

2022

AIA Next LA Design Honor Award

for the Dark Chalet2020

AIA Next LA Merit Award

for Orange Barrel Media Headquarters2020

AIA Next LA Design Honor Award

for the Sunset Spectacular2017

Los Angeles Business Council Design Award

for Main Museum of Los Angeles Art2017

Chicago Athenaeum American Architecture Award

for Main Museum of Los Angeles Art2017

Nominated for the USA Artists Award

2016

Winner of the West Hollywood Sunset Spectacular Competition

2016

AIA Next LA Design Award

for The Main Museum of Los Angeles Art2015

AIA Next LA Design Honor Award

for Kinmen Passenger Service Center2014

Second Prize, Stage II, Kinmen Passenger Service Center Competition

open International competition2014

Winner, MoCA Pavilion for The New Sculpturalism Competition

Invited competition2013

First Prize, Shenyang Civic Sports Center Competition

Invited competition2011

AIA Award winner, ARCH_IS ‘Young Architectural Talent’ Award

2010

‘Best and Brightest’, Esquire Magazine

2009

ICON Magazine’s ‘20 Architects Who Will Shape the Future’

2010

Selected as one of ICON Magazine‘s ‘50 Most Influential Design Practices’

2008

Second Prize in Novosibirsk Pavilion Competition

Open international competition2007

Finalist, Stage II, Czech National Library Competition

Open international competition2007

Second Prize in Seoul Performing Arts Center Competition

Open international competition2005

Second Prize in Seoul Performing Arts Center Competition

Open international competition2005

Architectural League Young Architect’s Prize

2004

2004 NY Engineering Awards - Platinum Award for P.S.1

2003

MoMA/ P.S.1 Young Architect Award

2003

Publications

Theory & Writings

A FLAT ONTOLOGY OF ARCHITECTURE

2024

A flat ontology of architecture is a way of seeing the world as a collection of lively, complete entities that cannot be reduced to universal elements or systems. While it cannot be codified into a singular language, it points to an architectural style in the broadest sense.

Architecture today is often designed as a hierarchical exercise in which: components build up into mass; outside dictates inside; form trickles down from function; context dictates architectural form. So much mindless subservience!

TWA approaches architecture, instead, as if all of its parts were laid out on a flat playing field... imagine a collection of toys on a table. Each part can be operated on independently from the others, and each is treated as a unique and lively entity in its own right.

Interiors are separated from exteriors, each developing its own features independent of the other. Tectonic and ornamental surface effects can deploy freely with or against the grain of architectural mass, following their own logic. Building circulation, rather than gluing functions together, can be extracted and shaped as independent entities. Grounds, rather than neutral receptors of buildings, can multiply independently of the earth-datum, inside or outside building boundaries.

The discreteness of these parts-- interiors, exteriors, circulation, facades, grounds, and many others-- creates tension and liveliness across architectural compositions, and unsettles our sense of the world as one big articulated lump of matter. A better world model for this century is one based on what philosopher Levi Bryant calls a “democracy of objects,” where all things exist equally but differently in the world. Buildings, landscapes, snowflakes, apples, cities, stardust, memes, mountains, bioluminescent algae, glass, supercars, galaxies-- can be regarded equally, without subjecting them to vertical relations and categories.

Architecture thus becomes a playful act of collecting, curating, and composing discrete, independent things (and their interfaces), rather than some form of wizardry where nondescript matter is pulled from the earth and subjected to all-too-human hierarchical patterns of thought founded in power relations. This is the true ecological thought for architecture today, founded in kindness.

IT'S TIME TO STOP WORRYING AND LEARN TO LOVE MEP

2025

MEP systems are a huge part of a buildings, and often 25-30% of their construction cost. Yet the MEP space is very short on conceptual ideas. Yes there has been some movement on natural ventilation and renewable energy in the last 25 years, but that makes up a small part of MEP systems in buildings. The majority of MEP systems are bramble bushes of metal ductwork, wet piping, and wiring, often conflicting with structural systems and breaching architectural cavities.

What we see of MEP is usually at its outermost tips- diffusers, access panels, and sprinkler heads breaching architectural surfaces. Sometimes we see exposed ducts if the architect is invested in fetishizing 20th century techno-mechanical aesthetics, which is anachronistic at this point. The rest of the equipment resides in the darkness of floor cavities and cores, suppressed from the visible world, which is maybe why it is so often left untheorized. You could say out of sight, out of mind, if it were not for the negative impacts of MEP in lost floor area, head height, endless design coordination hours, and cost. It also has to be said that so much of MEP is driven by prescriptive building code, the requirements of which have gotten entirely out of hand and can be daunting for even the best MEP engineers. These onerous requirements make the problem one of the state and not one of design, and must be addressed as a form of bureaucratic resistance.

Aesthetics can change the way we think about MEP. We need x-ray vision to see the kit stuffed into buildings, which is one reason TWA has been illustrating all of the building systems in architecture equally, and simultaneously, in our giant Godzilla cutaway drawings. By aesthetics I don't mean we should aestheticize mechanical and electrical systems, but rather that we should use our compositional skills to help determine clear pathways, bundle things together, and create hierarchies for systems in ways that do not conflict with architecture and other systems. Just look at the development of the SpaceX Raptor engine over the past 10 years alone-- this shows a fast shift from 20th century engineering to the 21st, which has to be argued in aesthetic as well as engineering terms. The simplicity and strong silhouette of the Raptor 3 engine vs. the 20th c. ball of wires and ducts of Raptor 1 shows how they go hand in hand. This new aesthetic territory is defined by its movement from line to mass, from field to strong graphic silhouette, and from complexity and contradiction to integration and serenity. Increasingly, when you look at humanity's best design objects, you see this swerve-- the graphic guts of an iPhone 14, the total integration of the B-2 Stealth Bomber-- and you realize how far behind architecture is.

We need global overview, not local problem solving. We need to act early in the design process, rather than later, when solutions will always be a messy retrofit. We need to rethink cores as Z-extrusions in favor of three-dimensional integrated core-objects, horizontal, inclined, and vertical, with their own aesthetics and inner life. Tendrils and spider webs should be woven into integrated braids of tech. Giant channels should be designed into floors, in a way that the infrastructural backbone of a building can be replaced when obsolete, like an automotive wiring harness. Fine-grained vector systems like sprinklers, chilled piping, and electrical conduit should be embedded in architectural surfaces. Ultimately, MEP systems need to be raised up in the building system hierarchy and be given new respect and care. I hesitate to call this approach sustainable design, because of the hollowness of that term today, but it is the only way to get past LEED brownie points toward a comprehensive new way of thinking about the relations of technology and architecture for the 21st century.

While BIM (building information modeling) has ostensibly changed the game by allowing us to see and deconflict MEP systems, it is truly surprising that this superior vision has not really changed much in terms of catalysing big new ideas about building infrastructure. "Clash detection" processes are used to resolve local clashes before they are discovered on site, in a case by case, battle by battle mode, and always toward the end of projects, when comprehensive evolution is no longer possible. Project administration is not design, it is just a way of muddling through problems whose source lies at an entirely different scale. Late administration urgently needs to be replaced with early, brave compositional moves, an ethos of extreme integration, and a sense of play. It's time to stop worrying and learn to love MEP.

What we see of MEP is usually at its outermost tips- diffusers, access panels, and sprinkler heads breaching architectural surfaces. Sometimes we see exposed ducts if the architect is invested in fetishizing 20th century techno-mechanical aesthetics, which is anachronistic at this point. The rest of the equipment resides in the darkness of floor cavities and cores, suppressed from the visible world, which is maybe why it is so often left untheorized. You could say out of sight, out of mind, if it were not for the negative impacts of MEP in lost floor area, head height, endless design coordination hours, and cost. It also has to be said that so much of MEP is driven by prescriptive building code, the requirements of which have gotten entirely out of hand and can be daunting for even the best MEP engineers. These onerous requirements make the problem one of the state and not one of design, and must be addressed as a form of bureaucratic resistance.

Aesthetics can change the way we think about MEP. We need x-ray vision to see the kit stuffed into buildings, which is one reason TWA has been illustrating all of the building systems in architecture equally, and simultaneously, in our giant Godzilla cutaway drawings. By aesthetics I don't mean we should aestheticize mechanical and electrical systems, but rather that we should use our compositional skills to help determine clear pathways, bundle things together, and create hierarchies for systems in ways that do not conflict with architecture and other systems. Just look at the development of the SpaceX Raptor engine over the past 10 years alone-- this shows a fast shift from 20th century engineering to the 21st, which has to be argued in aesthetic as well as engineering terms. The simplicity and strong silhouette of the Raptor 3 engine vs. the 20th c. ball of wires and ducts of Raptor 1 shows how they go hand in hand. This new aesthetic territory is defined by its movement from line to mass, from field to strong graphic silhouette, and from complexity and contradiction to integration and serenity. Increasingly, when you look at humanity's best design objects, you see this swerve-- the graphic guts of an iPhone 14, the total integration of the B-2 Stealth Bomber-- and you realize how far behind architecture is.

We need global overview, not local problem solving. We need to act early in the design process, rather than later, when solutions will always be a messy retrofit. We need to rethink cores as Z-extrusions in favor of three-dimensional integrated core-objects, horizontal, inclined, and vertical, with their own aesthetics and inner life. Tendrils and spider webs should be woven into integrated braids of tech. Giant channels should be designed into floors, in a way that the infrastructural backbone of a building can be replaced when obsolete, like an automotive wiring harness. Fine-grained vector systems like sprinklers, chilled piping, and electrical conduit should be embedded in architectural surfaces. Ultimately, MEP systems need to be raised up in the building system hierarchy and be given new respect and care. I hesitate to call this approach sustainable design, because of the hollowness of that term today, but it is the only way to get past LEED brownie points toward a comprehensive new way of thinking about the relations of technology and architecture for the 21st century.

While BIM (building information modeling) has ostensibly changed the game by allowing us to see and deconflict MEP systems, it is truly surprising that this superior vision has not really changed much in terms of catalysing big new ideas about building infrastructure. "Clash detection" processes are used to resolve local clashes before they are discovered on site, in a case by case, battle by battle mode, and always toward the end of projects, when comprehensive evolution is no longer possible. Project administration is not design, it is just a way of muddling through problems whose source lies at an entirely different scale. Late administration urgently needs to be replaced with early, brave compositional moves, an ethos of extreme integration, and a sense of play. It's time to stop worrying and learn to love MEP.

ARCHITECTURALIZING LANDSCAPE

2025

We often hear about “landscape architecture,” without a clear definition of how this is different from “landscape design” or even from “landscaping.” This lack of clarity is not a problem of language but rather a problem of ideas. The cultural discourse of landscape has fallen behind the discipline of architecture because it fails to explore and debate contemporary ideas about nature and science, instead often remaining in the vague realms of wilderness reconstruction, sustainability, and reiterating local ecologies. It fails to define nature as something distinct from science on the one hand and from outmoded philosophical ideas about nature on the other. It also fails to define clear aesthetic agendas for our time, which is strange because landscape design exists to show us what nature should look like when it is not found naturally occurring in the world.

One of the most suspicious claims we hear is that landscape design should mirror some primordial planetary state where things were untouched by humans; the problem with that is that there is no such thing. Humans have spent millennia engaged in both conscious and accidental terraforming of the planet through city-building, agriculture, domestication of animals, and deforestation.

At TWA, we are committed to the idea that all landscape is synthetic and therefore must have an independent aesthetic and ecological agenda that does not rely on origin stories. We have found that the best way to proceed is to architecturalize our thinking about landscape, forming our approach around objects and discreteness rather than the usual continuums and fields. We focus on strict boundaries, copy/scale language, stamping, and stark shapes over flows and gradients. An architecturalized landscape is one that is unapologetically based on terraforming the earth in ever more playful and aggressive ways, with all of the freedom and possibility that implies.

We believe that landscape architecture, in its currently weakened state, is ripe for radical transformation and debate. Our hope is that landscape design can shed developer expectations and decorator instincts, in a deep reconsideration of what “natural” means today. This will need to include rejection of over-simplified definitions of “ecology” as well, a term which is simultaneously overused and misunderstood. This is not a call for academic consideration, but for practicing landscape designers and architects to step up and show us shocking and beautiful landscapes of the future.

THROW IT DOWN

2024

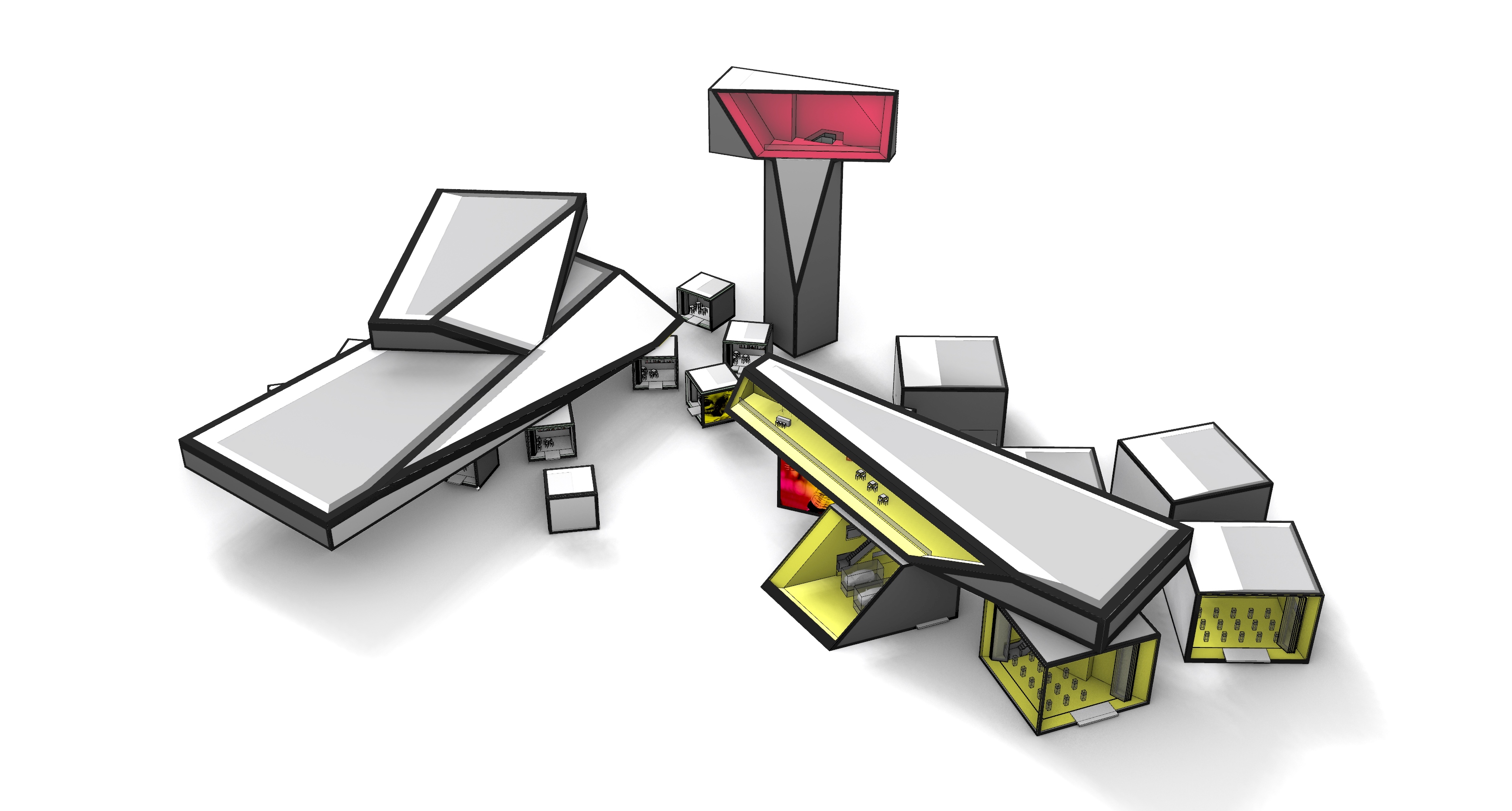

“Throw it down” is our office’s primary design method. It involves working with low-resolution chunks in quick iterations using discrete transformations. Although most of our work takes place in the computer, throwing things down, even if not literally with human hands, allows us to produce a sense of playful, effortless immediacy that is too easily lost in digital finessing.

Parts might be massive or tiny. They always appear as diverse collections and sometimes as copy-scale sets. However you see them, they will never be deformed, broken, or fused with other things. They persevere. The only ways we manipulate them are to move, rotate, scale, copy, and slice —that’s it. “Throw it down” means: don’t finesse a composition; make it fast and messy and don’t be afraid to jam things together.

Parts might be massive or tiny. They always appear as diverse collections and sometimes as copy-scale sets. However you see them, they will never be deformed, broken, or fused with other things. They persevere. The only ways we manipulate them are to move, rotate, scale, copy, and slice —that’s it. “Throw it down” means: don’t finesse a composition; make it fast and messy and don’t be afraid to jam things together.

DOWN TO EARTH

2024

TWA brings the wonder and mystery of the cosmos down to earth. We believe that architecture’s role in society is not to mirror the status quo, but rather to give glimpses into a better, more beautiful parallel universe. A parallel universe — unlike a truly alien one — draws us in through a combination of familiar and alien things that unsettle our habitual ways of being on earth.

Our projects are conceived as sets of lively, discrete objects that engage one another democratically and non-hierarchically. Our objects are not reductive, like sticks, bricks, or nails, but rather fully-formed and specific things like slabs, jacks, crystals, ziggurats, tesseracts, mountains, cities, and forests. Objects can be moved, rotated, scaled, or copied, but they can never be deformed or fused together, losing their identity.

We therefore operate as collectors and curators rather than sculptors or drafters. Our projects appear chunky, playful, provisional, and even sometimes like models built at full scale. The ecologies of objects that form our buildings set the stage for a new discussion of sustainability based on abundance rather than lack, where the world is not running out of everything but rather full of vibrant things that simply need to be oriented, organized, and thought about in new ways.

In our practice, everything is invented and nothing is taken for granted. We are committed to using our expertise in design, computation, construction, and energy intelligence to build a radical and hopeful future.

We believe that landscape architecture, in its currently weakened state, is ripe for radical transformation and debate. Our hope is that landscape design can shed developer expectations and decorator instincts, in a deep reconsideration of what “natural” means today. This will need to include rejection of over-simplified definitions of “ecology” as well, a term which is simultaneously overused and misunderstood. This is not a call for academic consideration, but for practicing landscape designers and architects to step up and show us shocking and beautiful landscapes of the future.

Our projects are conceived as sets of lively, discrete objects that engage one another democratically and non-hierarchically. Our objects are not reductive, like sticks, bricks, or nails, but rather fully-formed and specific things like slabs, jacks, crystals, ziggurats, tesseracts, mountains, cities, and forests. Objects can be moved, rotated, scaled, or copied, but they can never be deformed or fused together, losing their identity.

We therefore operate as collectors and curators rather than sculptors or drafters. Our projects appear chunky, playful, provisional, and even sometimes like models built at full scale. The ecologies of objects that form our buildings set the stage for a new discussion of sustainability based on abundance rather than lack, where the world is not running out of everything but rather full of vibrant things that simply need to be oriented, organized, and thought about in new ways.

In our practice, everything is invented and nothing is taken for granted. We are committed to using our expertise in design, computation, construction, and energy intelligence to build a radical and hopeful future.

We believe that landscape architecture, in its currently weakened state, is ripe for radical transformation and debate. Our hope is that landscape design can shed developer expectations and decorator instincts, in a deep reconsideration of what “natural” means today. This will need to include rejection of over-simplified definitions of “ecology” as well, a term which is simultaneously overused and misunderstood. This is not a call for academic consideration, but for practicing landscape designers and architects to step up and show us shocking and beautiful landscapes of the future.

STRATEGIES

2025

Chunkiness over Smoothness

Focus on discrete, raw shapes with clear boundaries. Avoid fusing things into continuums. Prioritize difference in kind over difference in degree.

Objects over Systems

Deploy objects only, one by one and with care, avoiding the generalizing meshworks and continuums of systems. Try objectifying things you thought were systems, like circulation or structure.

Entities over Elements

Invent lively, composite entities rather than breaking architecture down into universal, atomic parts. Architecture is not elemental.

Collections over Taxonomies

Put all of the parts of each project on a flat plane, like a kit or set. Concentrate on affinities rather than categories. Include hard parts like masses and soft parts like trees-- together they make the world of a building.

Abundance over Lack

Keep adding things to the mix as you work-- excess is what differentiates architecture from building. Efficiencies will come later.

Composition over Ordering

Move and scale independent components until they create a sense of visual cohesion without fusing together. Architecture is closer to play than math.

Nesting over Subdividing

Nest whole objects inside one another rather than treating interiors as homogenous space to be subdivided by floors and walls.

Copy/scale over Variation

Copy/scale is a fresh, lively, almost out of control aesthetic; variation always looks like the algorithm that made it.

Familiar and Alien

The best architecture is not a muddled ‘new’. It is always a hybrid of things we know combined with unknown, alien things.

Depth over shallowness

Give architecture spatial and sectional depth. Architecture is not an image.

The Plan is not the Generator

Plan drawings confuse architects about their primary role in society: to show us what the world should look like. Functional ordering is of secondary importance, and the purview of engineers.

Low-res over High-definition

Slabs, bars, ziggurats, tesseracts, stars, jacks all have an ancient resonance and combine in raw, provisional ways, whereas high-def shows you what you already know about the world.

Mystery over Representation

Create ambiguity and doubt as to a thing’s purpose in the world. Architecture is not a sign.

Discrete Transformations over Deformation

Copy, scale, rotate unsettles expected scales and orientations. Deformation harms objects and is always a critique of what is.

Invention over Critique

Architecture that is a critique of society will only ever be bad art. Architecture exists to re-invent society by pushing the boundaries of what might be, in terms of space, scale, aesthetics, technology and construction.

Joints over Connections

Joints reveal a world of vibrating, independent parts with provisional associations. Gaps present opportunities.

Models over Drawings

Embody projects in chunky, playful models rather than developing them through flat picture planes from another era.

Embrace Leaps over Slow Evolution

Do not be afraid of volatility. Throw things out if they are not working; you can’t tweak or finesse your way out of a weak concept. Architecture is about the big moves, not pulling polygon points.

Focus on discrete, raw shapes with clear boundaries. Avoid fusing things into continuums. Prioritize difference in kind over difference in degree.

Objects over Systems

Deploy objects only, one by one and with care, avoiding the generalizing meshworks and continuums of systems. Try objectifying things you thought were systems, like circulation or structure.

Entities over Elements

Invent lively, composite entities rather than breaking architecture down into universal, atomic parts. Architecture is not elemental.

Collections over Taxonomies

Put all of the parts of each project on a flat plane, like a kit or set. Concentrate on affinities rather than categories. Include hard parts like masses and soft parts like trees-- together they make the world of a building.

Abundance over Lack

Keep adding things to the mix as you work-- excess is what differentiates architecture from building. Efficiencies will come later.

Composition over Ordering

Move and scale independent components until they create a sense of visual cohesion without fusing together. Architecture is closer to play than math.

Nesting over Subdividing

Nest whole objects inside one another rather than treating interiors as homogenous space to be subdivided by floors and walls.

Copy/scale over Variation

Copy/scale is a fresh, lively, almost out of control aesthetic; variation always looks like the algorithm that made it.

Familiar and Alien

The best architecture is not a muddled ‘new’. It is always a hybrid of things we know combined with unknown, alien things.

Depth over shallowness

Give architecture spatial and sectional depth. Architecture is not an image.

The Plan is not the Generator

Plan drawings confuse architects about their primary role in society: to show us what the world should look like. Functional ordering is of secondary importance, and the purview of engineers.

Low-res over High-definition

Slabs, bars, ziggurats, tesseracts, stars, jacks all have an ancient resonance and combine in raw, provisional ways, whereas high-def shows you what you already know about the world.

Mystery over Representation

Create ambiguity and doubt as to a thing’s purpose in the world. Architecture is not a sign.

Discrete Transformations over Deformation

Copy, scale, rotate unsettles expected scales and orientations. Deformation harms objects and is always a critique of what is.

Invention over Critique

Architecture that is a critique of society will only ever be bad art. Architecture exists to re-invent society by pushing the boundaries of what might be, in terms of space, scale, aesthetics, technology and construction.

Joints over Connections

Joints reveal a world of vibrating, independent parts with provisional associations. Gaps present opportunities.

Models over Drawings

Embody projects in chunky, playful models rather than developing them through flat picture planes from another era.

Embrace Leaps over Slow Evolution

Do not be afraid of volatility. Throw things out if they are not working; you can’t tweak or finesse your way out of a weak concept. Architecture is about the big moves, not pulling polygon points.

STRUCTURE IS NOT AN OBJECT OF ARCHITECTURE

2025

Structure is everywhere all the time. It has no shape or silhouette, which architecture always has against the sky. While a field can be an object, structure is a weak field, with little impact on architectural form, unless the architect either loses control of it or insists on expressing it in defiance of mass. Sadly, the presence of visible structure is often an expression of fear or risk management. A great building, we think, is one that is instead an expression of magic and wonder.

Structure, and its bedfellows mechanical and electrical systems, should be concealed, embedded into foreground objects, never standing alone like technological skeletons that too often point to the limits of 20th century technology. Today, we have so many ways of concealing and embedding structure into surfaces, 2-way plates, composites, and prefabricated components. Structural analysis software and AI allow us to remove offending columns and redistribute forces in ways that do not emphasize gravity. This is not the time of simple spans and linear thinking, it is the time of confidence and imagination.

How a building lands on the ground is the most critical decision an architect makes. Structure always has a way of appearing at this last moment of separation, gluing buildings to the earth. We prefer buildings that hover, maintaining tension and separation with the earth, as if docking with it for a moment.

Our approach is to forcefully engage in structural thinking to be able to have choice and freedom in our work. We’ve drawn structure (and MEP) into our office against the grain of practice, which is busy giving all architecture’s core competencies away. It sometimes takes a while for our engineers to track with us, because we model every system and seem to be operating outside our lane, but then they realize that the total integration we seek requires it. Our goal is an architecture made of mysterious, composite objects, with articulation driven not by structural musculature but by free, invented architectural aesthetics.

In everyday practice, we often deal with errant sticks of structure threatening to undermine this architectural idea by radically scaling them up into mass, scuttling their reading as vectors. Or we tuck supports back just far enough into the shadows that they are not legible to the distracted viewer. In any case, all vertical lines into the earth must be interrupted. Such acts of embedding, scaling, concealing, or backgrounding structure can be effective in demoting the earth’s gravitational axis and the assumed primacy of structure in our discipline. It is ironic that architects have to be very good engineers to achieve this!

Structure, and its bedfellows mechanical and electrical systems, should be concealed, embedded into foreground objects, never standing alone like technological skeletons that too often point to the limits of 20th century technology. Today, we have so many ways of concealing and embedding structure into surfaces, 2-way plates, composites, and prefabricated components. Structural analysis software and AI allow us to remove offending columns and redistribute forces in ways that do not emphasize gravity. This is not the time of simple spans and linear thinking, it is the time of confidence and imagination.

How a building lands on the ground is the most critical decision an architect makes. Structure always has a way of appearing at this last moment of separation, gluing buildings to the earth. We prefer buildings that hover, maintaining tension and separation with the earth, as if docking with it for a moment.

Our approach is to forcefully engage in structural thinking to be able to have choice and freedom in our work. We’ve drawn structure (and MEP) into our office against the grain of practice, which is busy giving all architecture’s core competencies away. It sometimes takes a while for our engineers to track with us, because we model every system and seem to be operating outside our lane, but then they realize that the total integration we seek requires it. Our goal is an architecture made of mysterious, composite objects, with articulation driven not by structural musculature but by free, invented architectural aesthetics.

In everyday practice, we often deal with errant sticks of structure threatening to undermine this architectural idea by radically scaling them up into mass, scuttling their reading as vectors. Or we tuck supports back just far enough into the shadows that they are not legible to the distracted viewer. In any case, all vertical lines into the earth must be interrupted. Such acts of embedding, scaling, concealing, or backgrounding structure can be effective in demoting the earth’s gravitational axis and the assumed primacy of structure in our discipline. It is ironic that architects have to be very good engineers to achieve this!

TECTONIC FICTIONS

2025

Architects today too often operate in a mode of selection rather than invention, as if we have no control over construction and materials anymore. Our position is that architects must lead in the realm of tectonics precisely because industry is economically invested in producing what it is already tooled up to do; without architects, construction can’t evolve.

TWA is on a special mission against what we call “articulation for free” which is basically what happens to architecture when the architect relies on existing systems and materials to produce effects. There are all kinds of articulation for free, from bricks and mortar to cast-in-place concrete, to standard metal panel and glazing systems, on and on. Architectural effects become so much less magical when buildings are designed as compilations of these kinds of articulation. A better role for architects is as inventors, rather than managers of products. This is how Le Corbusier broke through with his Villa Savoye.

![]()

Architecture that mirrors known construction tries to convince us that the everyday reality which surrounds us is the only reality possible. This is not the highest and best use of our expertise. Architecture ought to aim to challenge the world we often uncritically accept, and to show us that other forms of reality are possible. Articulation for free is therefore not free at all; it costs our discipline its autonomy and reduces its space of invention.

There are many different approaches we’ve used to create what we call “tectonic fictions” instead of accepting articulation for free, or worse, tectonic “truth.” Fake or suppressed joints, huge panels, exaggerated structure, fake shadows and reflections, and cartoon silhouettes are all part of our toolbox intended to undermine tectonic expectations.

Tattoos slide around on forms, sometimes emphasizing, sometimes de-emphasizing features, and creating a second or ambiguous reading of forms. Metaseams are graphic seams that may or may not be related to tectonic joints. They tend to visually break mass down into very large pieces, unsettling our reading of scale. Supercomponents are components of buildings like giant model kit parts, with radically different sizes and shapes and embedded building systems. Tectonic fictions, if they are to be believed, require a magician’s sleight of hand with the technology of the day.

TWA is on a special mission against what we call “articulation for free” which is basically what happens to architecture when the architect relies on existing systems and materials to produce effects. There are all kinds of articulation for free, from bricks and mortar to cast-in-place concrete, to standard metal panel and glazing systems, on and on. Architectural effects become so much less magical when buildings are designed as compilations of these kinds of articulation. A better role for architects is as inventors, rather than managers of products. This is how Le Corbusier broke through with his Villa Savoye.

Architecture that mirrors known construction tries to convince us that the everyday reality which surrounds us is the only reality possible. This is not the highest and best use of our expertise. Architecture ought to aim to challenge the world we often uncritically accept, and to show us that other forms of reality are possible. Articulation for free is therefore not free at all; it costs our discipline its autonomy and reduces its space of invention.

There are many different approaches we’ve used to create what we call “tectonic fictions” instead of accepting articulation for free, or worse, tectonic “truth.” Fake or suppressed joints, huge panels, exaggerated structure, fake shadows and reflections, and cartoon silhouettes are all part of our toolbox intended to undermine tectonic expectations.

Tattoos slide around on forms, sometimes emphasizing, sometimes de-emphasizing features, and creating a second or ambiguous reading of forms. Metaseams are graphic seams that may or may not be related to tectonic joints. They tend to visually break mass down into very large pieces, unsettling our reading of scale. Supercomponents are components of buildings like giant model kit parts, with radically different sizes and shapes and embedded building systems. Tectonic fictions, if they are to be believed, require a magician’s sleight of hand with the technology of the day.

THE PROBLEM OF SUBDIVISIONS

2025

The process of designing, detailing, and creating working drawings for construction tends to be one of subdividing large things into small things that can be handled and transported. This has the side effect of impressing the human scale on buildings, which some may find satisfying, but we find problematic. Wouldn’t it be great if architecture didn’t resemble its everyday limits and traces of its manufacture, such as limits in metal panel, glass unit, and stone sizes?

We are by no means arguing for a fantasy project, where materiality is ignored- that is a sure way to have no effect on architecture in the world. What we are rooting for is the idea of architects controlling subdivisions in buildings by suspending the aesthetic relation to humans. This allows us to control the reading of scale which is one of the most powerful effects in architecture. Was it built by giants? By aliens? How was this made and for whom? This approach requires us to rethink the outsized power standardized systems have come to have over our design thinking. It’s time to stop shopping and selecting and start inventing-- we have given away too much.

Another, maybe more fundamental, issue we have with subdivision thinking is the way internal spaces of buildings are often broken up by packing them with floors and walls, like an apple cut with an apple-cutter. We prefer the idea of objects nested within objects over infilling and packing. This approach produces a loose, playful relationship between architectural containers and their interior compartments, and between compartments and other compartments. Radically different scales of space and interstitial realms can be created, allowing for unexpected diagonal views and circulation of people, air, and light. Imagine spaces inside buildings that are vast and three-dimensional like mountain ranges or coral reefs. A snow globe is maybe the best metaphor for two reasons: one, it is a container of independent worlds, and two, its inner objects never conform to their container. In any case, we propose that floors should not be treated like infill trays cut at mass edges, but rather be constrained to internal objects, leaving gaps. Walls should never infill between floors as if every level is a different Revit game board; they should have vertical continuity where possible to create vertiginous spaces.

Within the age-old discussion of part-to-whole relations in architecture, this is an appealing new avenue: things can be simultaneously an independent thing and a part of something else. Think of things inside of things inside of things all the way down, from universes to galaxies to planets to bodies to molecules to cells, on and on: none of these is lesser than the other just because it is smaller--each thing has its own aesthetics and life. This flattened relationship has been referred to by contemporary philosopher Levi Bryant as a “strange mereology”-- mereology, as in the study of part-to-whole relations, and strange because this approach denies hierarchies in our understanding of everything in the world, in favor of everything existing equally but differently. The ubiquitous statement that “the whole is greater than the parts” is thrown out the window.

We are by no means arguing for a fantasy project, where materiality is ignored- that is a sure way to have no effect on architecture in the world. What we are rooting for is the idea of architects controlling subdivisions in buildings by suspending the aesthetic relation to humans. This allows us to control the reading of scale which is one of the most powerful effects in architecture. Was it built by giants? By aliens? How was this made and for whom? This approach requires us to rethink the outsized power standardized systems have come to have over our design thinking. It’s time to stop shopping and selecting and start inventing-- we have given away too much.

Another, maybe more fundamental, issue we have with subdivision thinking is the way internal spaces of buildings are often broken up by packing them with floors and walls, like an apple cut with an apple-cutter. We prefer the idea of objects nested within objects over infilling and packing. This approach produces a loose, playful relationship between architectural containers and their interior compartments, and between compartments and other compartments. Radically different scales of space and interstitial realms can be created, allowing for unexpected diagonal views and circulation of people, air, and light. Imagine spaces inside buildings that are vast and three-dimensional like mountain ranges or coral reefs. A snow globe is maybe the best metaphor for two reasons: one, it is a container of independent worlds, and two, its inner objects never conform to their container. In any case, we propose that floors should not be treated like infill trays cut at mass edges, but rather be constrained to internal objects, leaving gaps. Walls should never infill between floors as if every level is a different Revit game board; they should have vertical continuity where possible to create vertiginous spaces.

Within the age-old discussion of part-to-whole relations in architecture, this is an appealing new avenue: things can be simultaneously an independent thing and a part of something else. Think of things inside of things inside of things all the way down, from universes to galaxies to planets to bodies to molecules to cells, on and on: none of these is lesser than the other just because it is smaller--each thing has its own aesthetics and life. This flattened relationship has been referred to by contemporary philosopher Levi Bryant as a “strange mereology”-- mereology, as in the study of part-to-whole relations, and strange because this approach denies hierarchies in our understanding of everything in the world, in favor of everything existing equally but differently. The ubiquitous statement that “the whole is greater than the parts” is thrown out the window.

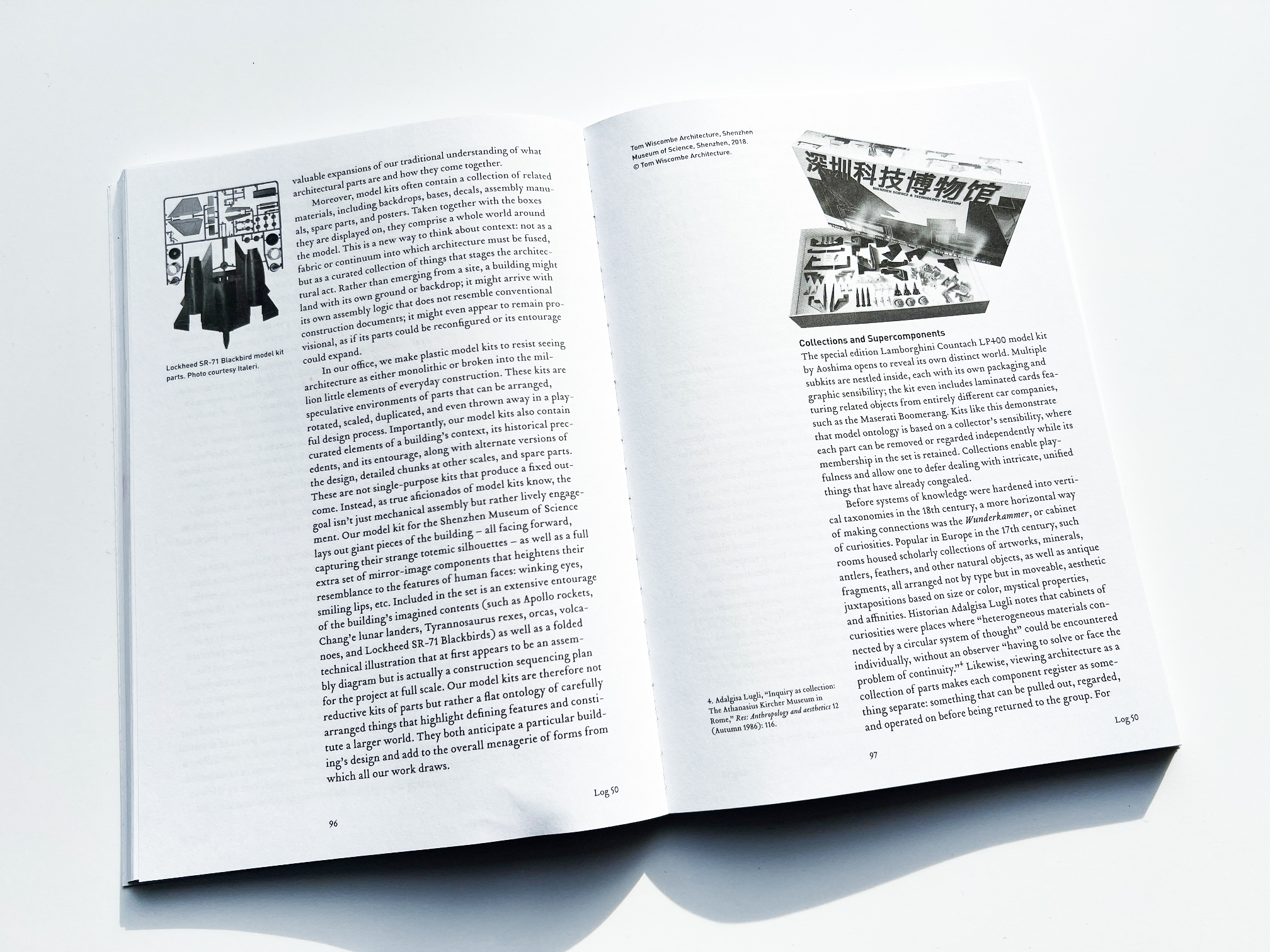

On Mass Vs. Graphics: A Conversation

Excerpted from Objects Models Worlds

On Mass Vs. Graphics

Joe Ledbetter / Tom Wiscombe

Tom Wiscombe I’m really excited about our ongoing project together — to think about what happens to architecture as a toy or a model, but also to think about a toy or model as architecture. One of the things that interests both of us is the relation between mass and graphics, and how graphics can be used to alter the reading of mass. Some graphic moves can reinforce boundaries, while others can create ambiguity. We both sometimes use fake reflections or shadows across objects to these ends. . . when did you start doing that?

Joe Ledbetter I’m really excited about this project as well. It’s challenging and a bit out of my wheelhouse which makes it all the more thrilling. I know I’m still trying to wrestle with the idea of architecture as a toy and a toy as architecture. Where do the definitions overlap? Maybe definitions are too limiting? In any case, I can’t wait to really tackle this together.

I began playing with artificial highlights and shadows when I first began to work in 3D back in 2004. I stumbled across this idea as I was trying to replicate 2D characters from my paintings into designer toys. I instantly found it created a really unique and interesting look — something that stood out from the crowd. Holding the toy in my hands, it seemed superimposed because it somewhat defied reality and the nature of light and the physical environment. It felt subversive against nature in a playful way.

Architecture however is an entirely different animal. You really have the opportunity to play on these massive scales and work with the sun, different times of the day, seasons, weather, hard shadows, etc., not to mention taking into account the angles at which people will see and experience the structures. You get to dictate how people view your work to some extent, though at the same time you can’t control when they will experience it. The variables seem a bit overwhelming to me. How much are you thinking about creating natural and artificial shadows, reflections, etc. while you’re designing? Are you thinking a lot about how natural shadows will cast? How much do you leave it up to chance and let the environment do whatever it’s going to do?

TW I totally agree that objects are so much more intriguing when they defy reality, or are as you say, are “subversive against nature.” Architectural design software reached a point about 20 years ago when it could perfectly recreate natural shadows, and that always bothered me. What is the purpose of mirroring reality as we already know it or modelling things we can easily predict? When I was a kid, I remember loving off-world sci-fi scenes where there were 10 moons or 3 suns, casting multiple shadows and reflections, and destabilizing “earthiness.”

So yes, at some point about 7 years ago, I started thinking about how to remove a building from its relational atmospheric network and put it in an alternate one. We invented what we called the “light studio” which was a kind of miniature digital stage where we lit digital models using all artificial lights. We used grids of fluorescents, fields of starlights, and even strange illuminated objects just out of the scene — all with the intent of defamiliarizing the way architecture reflects its context. We eventually took these shadows and reflections and physically embedded them into the architecture as different materials and facade types. When the building is built, you get the feeling that it is not quite meant for this world although it may exist in it.

It’s interesting that you began to anticipate 3D toy designs in your paintings, and that those shade/shadow effects somehow remained in the actual 3D object. What was a kind of strategy of increasing realism becomes a technique of speculative realism. It is a kind of magic trick, where at first you think you are seeing a figure with some features graphically emphasized, but you then realize that the graphics are actually destabilizing the figure, making it vibrate. Architecture is really hard to make vibrate like that! It is so big and there are so many cultural projections on it, and of course there is gravity that always keeps it pinned in place. Do you ever use fake gravity?

JL I’ve found that I have become more interested in defying gravity the longer I design toys. I suppose the limitations of gravity have always been a challenge for people throughout the ages. I love finding new ways to balance a toy or give the illusion that the figure is jumping or even flying. I’ve always felt that a static pose can often be quite boring.

Some of my favorite examples are my charging Ram, the “Pelican’t” and my Wolfgang figure who is leaping in excitement. A more recent project involves a stack of characters hitching a ride on a scooter. Here I am trying to create the sense of weight and movement, all while balancing an impossible stack of creatures. But none of that is using “fake gravity,” which I suppose is the opposite of defying it. By “fake gravity” you mean emphasizing and exaggerating weight and gravity’s effects?

TW For me the term “fake” implies a world of imagination rather than scientism where things follow known laws. I love the idea of gravities pulling massive and tiny things together but not the idea that it is a universalizing force pulling architecture into low, bottom-heavy structures close to the ground. That inadvertently sets everything into a hierarchy, and mirrors the quality of the earth as a bunch of matter sedimented around a point. I prefer quantum “spooky action at a distance” to gravity — all though they are both technically “laws” of physics, SAAD seems almost impossible. SAAD creates weird communications and mirroring effects between things that make the world seem animate and mysteriously ecological. I also love that the term “fake” adds a funny, lighthearted quality to “gravity” which is something very heavy and dark and serious, as in dark humor.

When I look at your Wolfgang figure, I see you not only defying gravity, but creating a kind of alternate physics. His tongue is heavy and hits the ground, but then his leg is weightless but poised and his skull and eyes are literally able to penetrate the shell of his body. The laws of gravity and recoil and magnetism all seem to be in play, and operating differentially rather than uniformly. It’s one thing when, in cartoon reality, Wiley Coyote tries to catch a flying anvil and his arms stretch out, but another when you make physical models like you do with everyday physics operating in the background. It’s a lot like how I try to “defer” landing in my architecture — through illusion and sleight of hand. I love the way you do that in your stack-of-figures piece, by setting it on a puffy cloud of dust (with stars). Great move. While rationally you know it’s a structural device, you just don’t care because its precariousness is what drives the imagination.

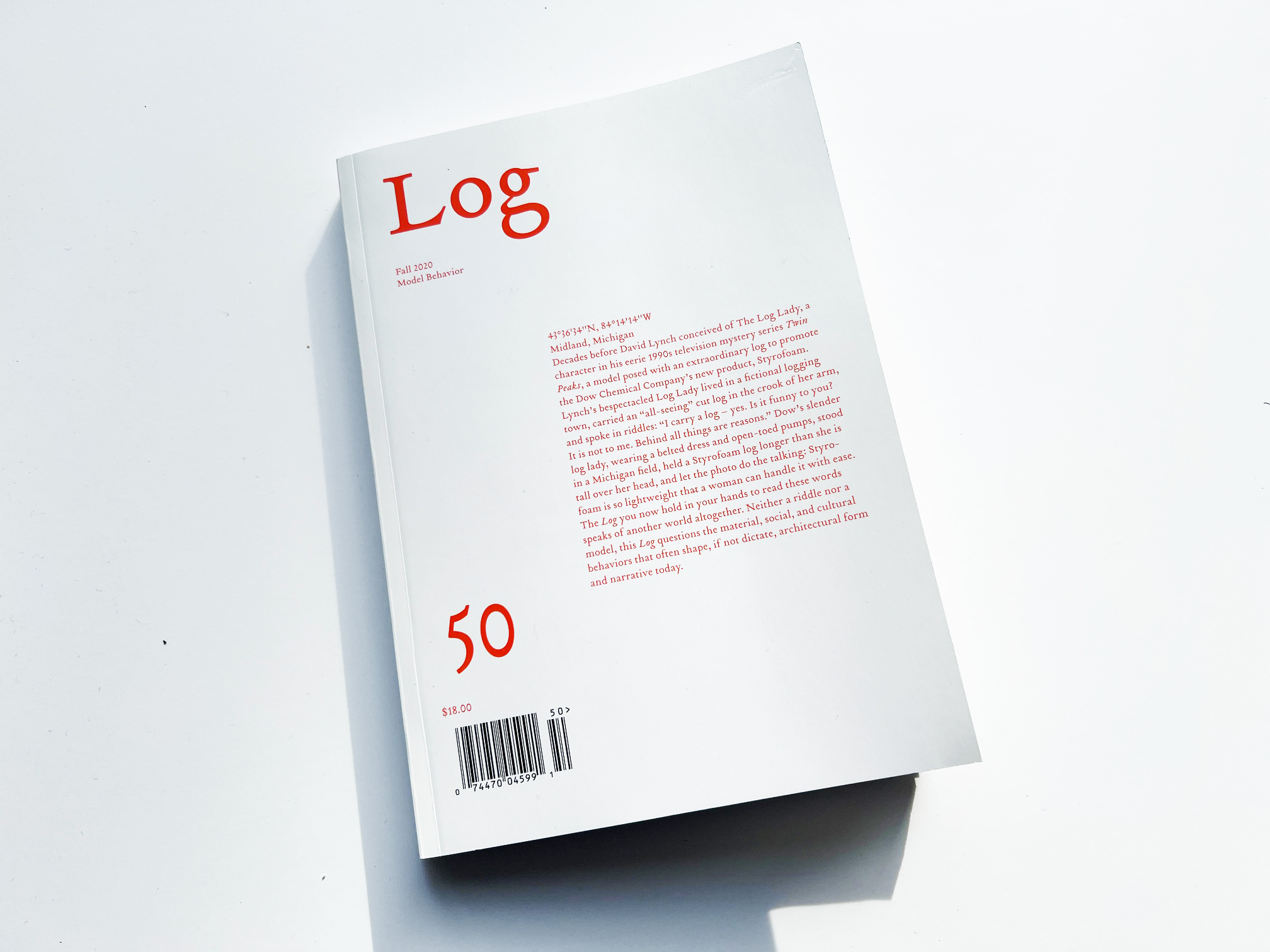

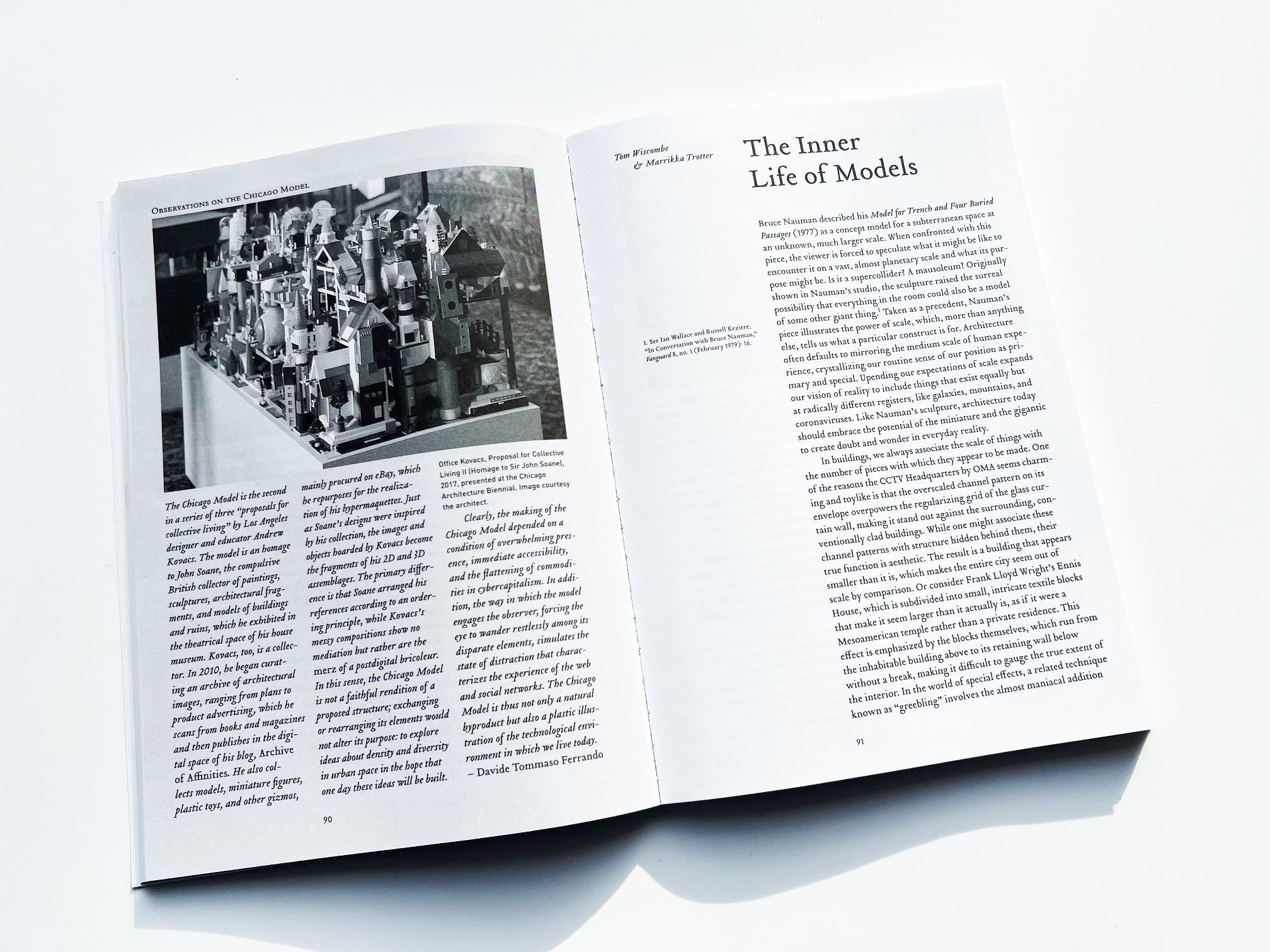

The Inner Life of Models

LOG 50: Model Behavior, Fall 2020

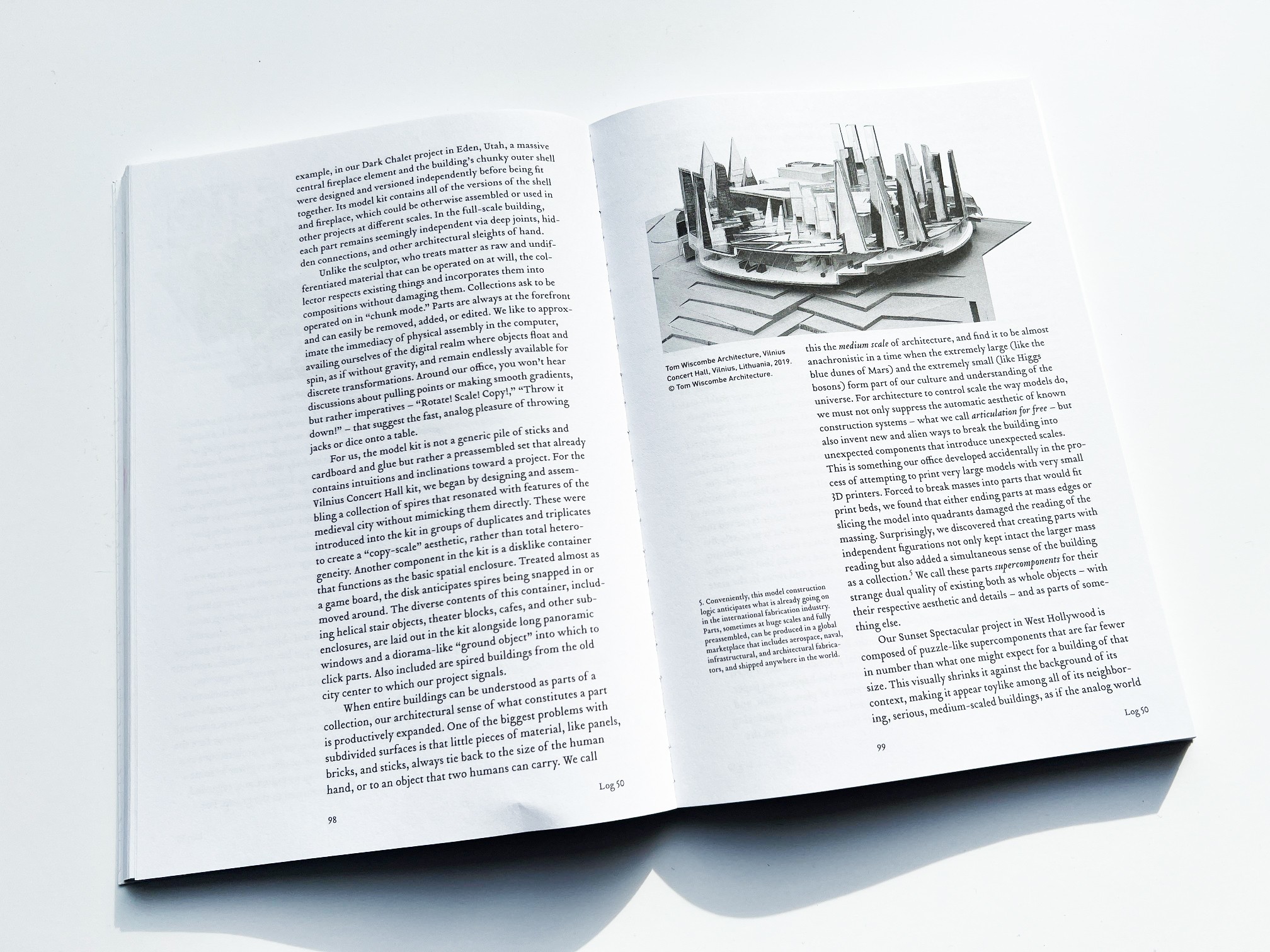

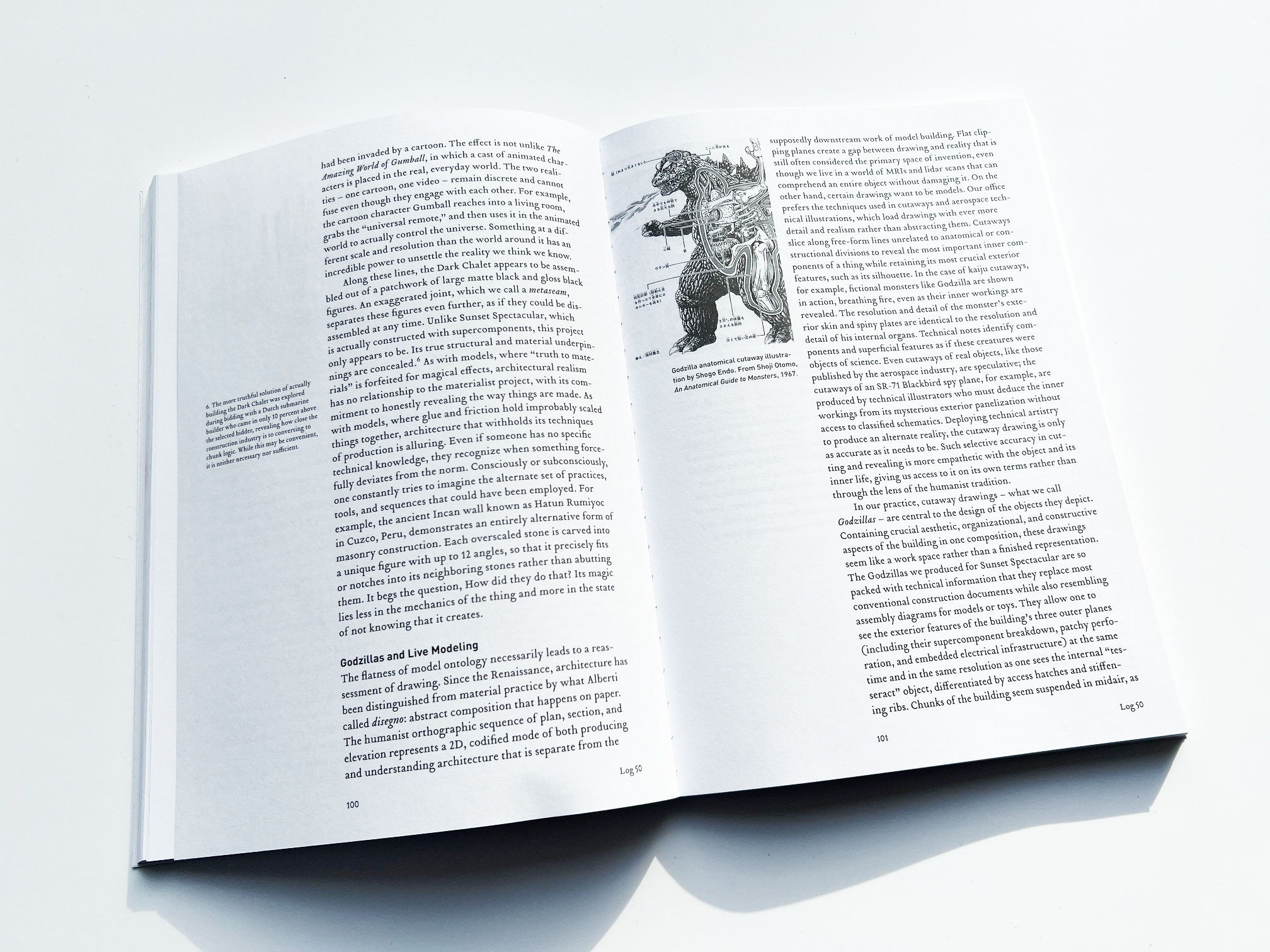

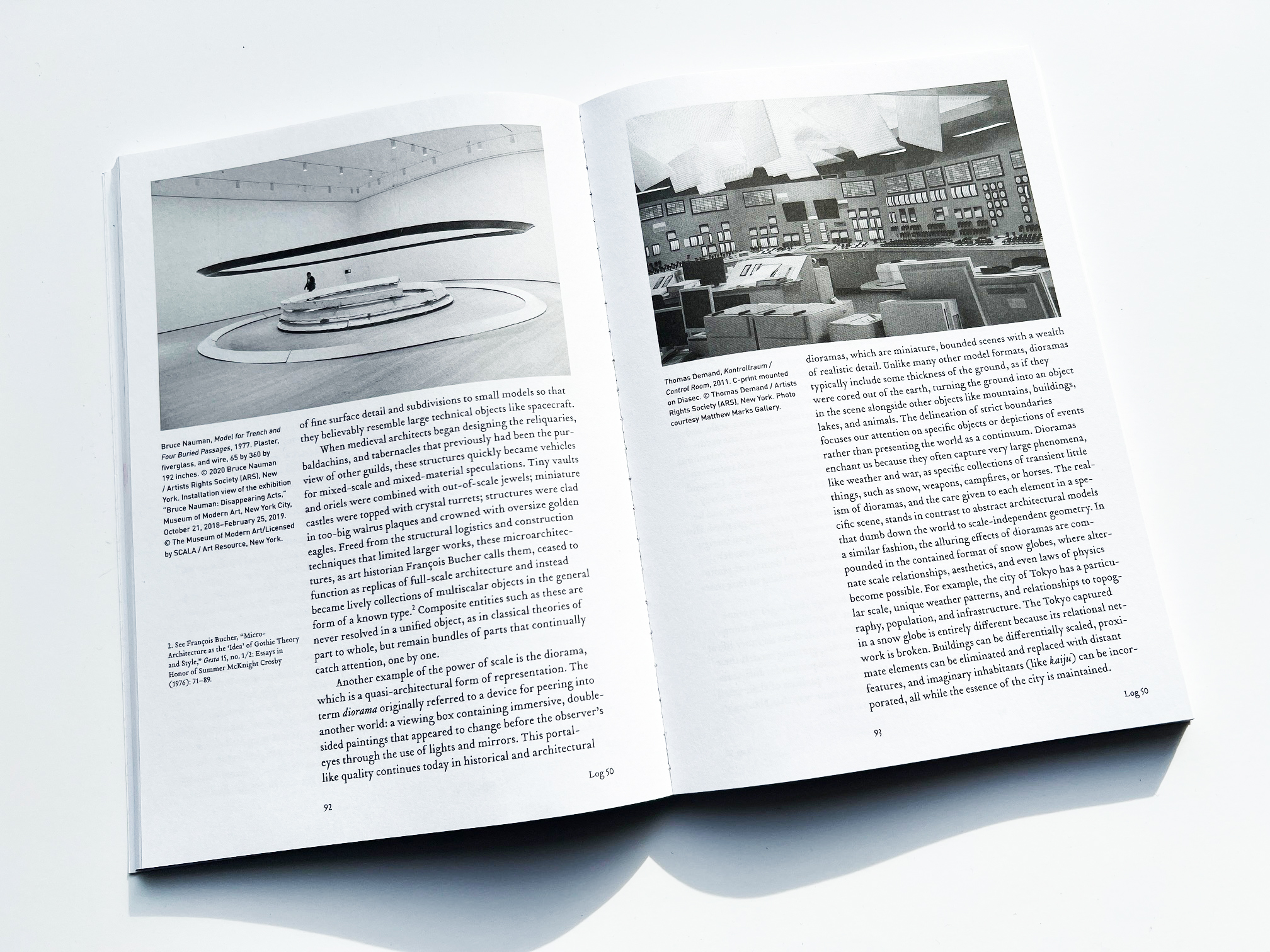

Bruce Nauman described his “Model for a Trench and 4 Buried Passages” (1979), as a concept model for a subterranean space at an unknown, “much larger” scale. When confronted with this piece, the viewer is forced to speculate what it might be like to encounter it on a vast, almost planetary scale, and what its purpose might be. Is it a supercollider? A mausoleum? Originally shown in Nauman’s studio, the sculpture raised the surreal possibility that everything in the room could also be a model of some other, giant thing. Taken as a precedent, Nauman’s piece illustrates the crucial power of scale, which tells us more than anything else what a particular construct is for. Architecture too often becomes a mirror of the human medium scale, crystallizing our routinized sense of our position as primary and special. Upending scale expands our vision of reality to include things that exist equally but on radically different registers, like galaxies, mountains, and corona viruses. Architecture today should embrace the potential of the miniature and the gigantic in our contemporary experience.